My interview for a Junior Research Fellowship was one of my last almost normal academic activities before the pandemic. Normal, in that I went into a room and talked to people about my research. Almost normal, in that it could never be normal to walk into an interview while in the middle of an international move: I had taken the overnight ferry from Dublin and left my family in our new home, surrounded by boxes. Last, because it was March 2020, and by the time I received the email inviting me to join the Linacre community, life had moved online – and so had my research.

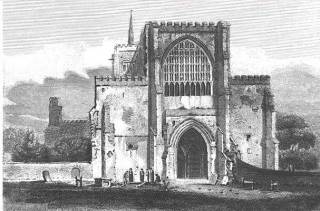

As it happens, many of the resources I need were already online. In a sweeping digitization programme, Google has processed vast quantities of nineteenth-century material, including obscure translations of medieval literature. This is what I’m interested in –specifically German adaptations of medieval English literature and English adaptations of medieval German. You might be asking why I’m spending my time on these largely-forgotten texts. The answer is that our contemporary understanding of the Middle Ages is filtered through the nineteenth century. This is as true of built heritage – Victorian so-called restorations of medieval parish churches, for example – as it is of literary heritage. Much of the best-known medieval literature today was rediscovered, translated, and edited during the long nineteenth century, the period between 1789 and 1914. None of this occurred in a political or social vacuum: writers, including those I’m studying, created distinct constructions of the medieval world specific to their own cultural-political contexts. They were writing with different, often strongly politicised, notions of Anglo-German cultural links and their own claims to the literature they were reworking. Because their work continues to influence how we think of the Middle Ages, research in this area is deeply relevant in today’s political climate, in which populist narratives depend on selective interpretations of medieval and modern history.

Nineteenth-century interpretations of medieval literature were produced for a wide range of audiences, from children to philologists. Some attempt to follow the medieval text word-for word; some don’t even try. Some are illustrated; others offer dizzying rows of black text. The occasional images of the hands of the people who scanned them are a twenty-first-century addition that never fails to raise a smile. I’m currently looking at translation strategies for dealing with obscenity in the Canterbury Tales. Chaucer’s readers have agonised for centuries over how to reconcile his (inter)national significance with his perceived indecency. A smile might also be an instinctive twenty-first-century response to the editor who insists that modern High German is simply too ‘decent’ a language for Chaucer’s particularly dirty passages, or the translator who replaces, not only so-called vulgarities, but also the most technical terms for ‘bottom’ with ellipsis. But setting aside our own twenty-first-century prejudices is necessary if we are to understand how previous societies dealt with questions that still trouble us today: the intersection of nationalism and art; offensiveness, censorship; difficult history. The desire to obscure those aspects of the past which make us feel uncomfortable is not a modern innovation.

Translations cannot give the full picture, and often endeavour not to. But there are other complications. I have been fortunate during the pandemic still to be able to access the words of these writers over a century ago, themselves echoing words hundreds of years older. But the digital world itself is also an echo. It cannot replicate the fullness of an in-person academic community, and a black-and-white scan can only tell us about the words on the page, not about the book to which it belongs. Life online is only half the story.

Mary Boyle, Leverhulme Early Career Fellow, Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages

Images

- The west end of St Alban’s Cathedral as it appeared in the early nineteenth century. Image from Beauties of England & Wales (London, 1805). Public domain.

- The west end of St Alban’s Cathedral as it appears today. Photo by David Iliff. License: CC BY-SA 3.0

- A technician’s hand, scanned on to one of the preliminary pages of Lydia Hands, Golden Threads from an Ancient Loom: das Nibelungenlied, adapted to the use of young readers (London, 1880). Scanned by Google, from a copy held in the Bodleian Library (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 UK).